This post contains affiliate links. We may earn a commission if you click on them and make a purchase. It’s at no extra cost to you and helps us run this site. Thanks for your support!

Good Design That Works: Learn About the Principles for Products That Delight Users and Respect the Planet

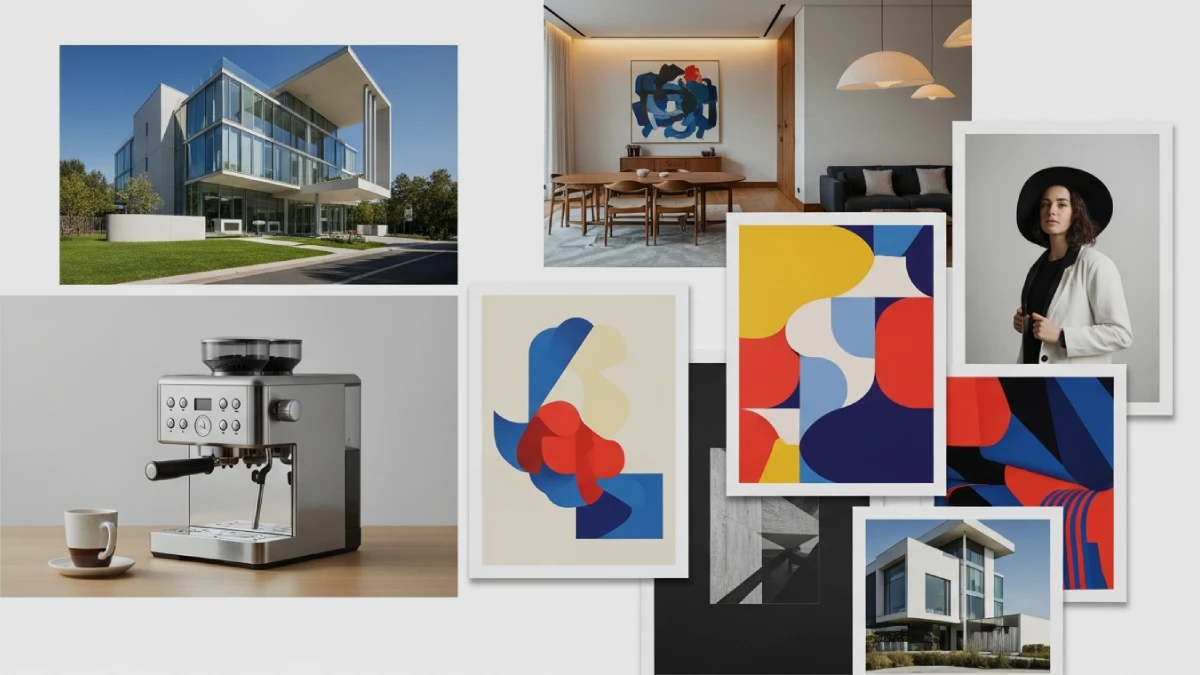

Good design is not a slogan; it is a promise that every detail has been considered and every decision serves a clear purpose. We interact with countless digital and physical artefacts every day, from the apps on our smartphones to the chairs we sit on. The quality of these interactions shapes our mood, productivity, and even our health. When a product fails, we notice the frustration immediately. When it succeeds, the experience feels so natural that we often forget to think about the design at all. With consumers more informed than ever and sustainability becoming a mandate rather than an option, it is worth asking: what makes good design truly good? This article explores the timeless principles that distinguish well‑designed products from the rest, drawing on classic principles, contemporary user‑centred thinking, and recent sustainability research.

Understanding Good Design

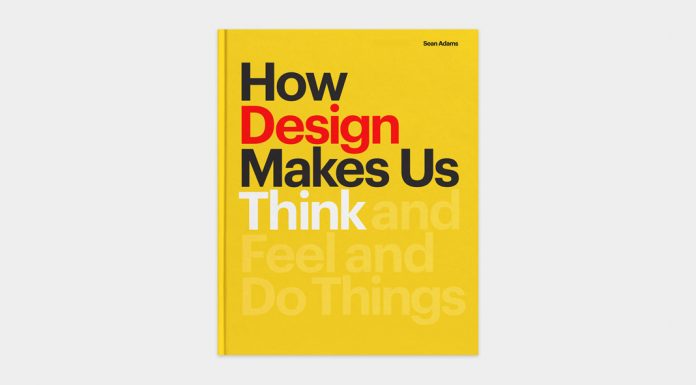

Good design is more than aesthetics. It influences our decisions, emotions, and values, and it can empower or exclude. Products that respect users feel effortless because they anticipate needs and remove barriers, while thoughtless design increases cognitive load and wastes time. In a world where competition is fierce and attention spans are short, companies that invest in good design see tangible benefits: improved loyalty, positive word‑of‑mouth, and higher conversion rates. A well‑designed experience returns far more than it costs. This is not just about profits—ethical design reduces waste, fosters inclusivity, and contributes to a more sustainable economy.

Designers working today operate at the intersection of creativity, technology, and ethics. To build something worthwhile, they must balance innovation with usability, efficiency with empathy, and aesthetics with sustainability. The following sections break down the key principles of good design into three categories: user‑focused principles, product and process principles, and broader impact principles. For each principle, we consider what it means, why it matters, and how designers can apply it to their work.

User‑Focused Principles

Innovative Design Is More Than Novelty

Innovation is often equated with novelty, yet novelty without purpose can lead to gimmicks. Classic design thinkers emphasise that good design is innovative because technology is always creating new possibilities. However, innovation should never be an end in itself; it must serve real human needs. Successful products like the first iPod or Dyson’s bagless vacuum cleaner did not simply add features; they used technology to solve persistent problems elegantly. When you consider a product or service, ask yourself: Does it introduce a breakthrough that makes a task easier or more meaningful? If not, a simpler, more thoughtful solution may be better.

Useful Design Satisfies Functional and Emotional Needs

A product is bought to be used. Useful design emphasises usefulness and avoids features that could detract from it. Utility is not just about function; it includes emotional satisfaction and psychological comfort. A coffee mug that feels good in the hand, a website that guides you effortlessly to what you need, or a chair that supports posture all demonstrate usefulness. The best design decisions come from understanding users’ needs and fulfilling them. To create useful products, designers should conduct in‑depth research, observe how people behave, and test prototypes with real users. Listening to feedback and iterating on designs ensures that the final product aligns with users’ goals and preferences.

Understandable Design Clarifies Structure

Complexity often hides behind an elegant façade. When designers say good design makes a product understandable, they mean it clarifies the structure so that the product “talks” and becomes self‑explanatory. In practice, this means a user should never have to devote thought to whether things are clickable or not. Clear visual hierarchy, consistent navigation, and intuitive controls reduce cognitive load. Using simple language rather than jargon also helps; writing in plain terms improves comprehension. Designers can achieve clarity by returning to basics—points, lines, and planes—as taught by the Bauhaus school. Sketching user flows and simplifying each interaction ensures that people can instantly understand what to do next.

Unobtrusive Design Respects the User

Tools should serve us without drawing attention to themselves. Products that fulfill a purpose are like tools; they should be neutral and restrained so users can express themselves. Unobtrusive design avoids decorative excess and focuses on the essentials. When a user interacts with a well‑designed application, they should feel empowered rather than overwhelmed. Minimalism is not about stripping features but about prioritising what truly matters. Consider the simplicity of Google’s homepage or the quiet elegance of Muji’s products. These examples show how good design can fade into the background while enhancing the user’s own experience.

Product and Process Principles

Aesthetic Quality Enhances Utility

Aesthetic appeal and function are inseparable. The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness. Beautiful objects attract us, but beauty alone cannot compensate for poor functionality. Rather, the execution of details—materials, proportions, color harmony—makes an object both appealing and usable. Designers should pay attention to textures, typography, and rhythm so that users enjoy interacting with the product. As our cultural and technological evolution redefines aesthetics, beauty aligns with respect for the planet. Contemporary aesthetics often include visible signs of sustainability, such as recycled materials or modular construction.

Honesty Builds Trust

When designers say good design is honest, they warn against making products appear more innovative, powerful, or valuable than they are. Overpromising leads to disappointment, erosion of trust, and unnecessary waste. Honest design communicates the true capabilities of a product. In software, this might mean avoiding dark patterns that trick users into subscriptions. In packaging, it could mean showing the actual size and contents. Honesty also involves transparency about sourcing and environmental impact. Brands that reveal their supply chains or use certification labels demonstrate integrity and encourage consumers to make informed choices. Designers should therefore collaborate with marketing teams to ensure that messaging aligns with reality.

Durability: Designing for Longevity

Throwaway culture harms the planet and undermines user trust. Good design avoids being fashionable so that it never appears antiquated, lasting many years even in today’s throwaway society. Long‑lasting design involves choosing durable materials, designing for repairability, and creating timeless aesthetics. Smartphones that support battery replacement, furniture with replaceable parts, and clothing made from quality fabrics are all examples. A long lifespan not only saves resources but also builds emotional attachment; users form relationships with products that age gracefully. For businesses, designing for durability fosters brand loyalty and reduces warranty claims.

Thoroughness Shows Respect

Attention to detail signals respect for the user. Nothing must be arbitrary or left to chance; care and accuracy in the design process show respect. Thorough design means evaluating every element—spacing, alignment, micro‑interactions—so that the experience feels polished. Consistency is vital; an inconsistent user experience forces people to relearn how to use a product after every update. Thoroughness also extends to content: ensuring that error messages are helpful, that instructions are easy to follow, and that accessibility features are built in. By sweating the details, designers eliminate friction and demonstrate care.

Broader Impact Principles

Environmentally Friendly Design Is Urgent

Sustainable design is no longer a niche topic; it has become a fundamental pillar in evaluating projects. The integration of environmentally friendly materials and optimisation of production processes now represent guiding principles of design. Designers and industries must assume responsibility to meet current environmental needs and preserve the future. Techniques such as life‑cycle analysis help assess environmental impact and identify ways to extend a product’s lifespan through repairability and modularity. Using recycled materials, bioplastics, and renewable resources reduces dependence on fossil fuels and offers new possibilities for recycling and reuse. Advanced production technologies like 3D printing and digital manufacturing optimise raw materials by reducing waste. In practice, sustainable design may involve selecting materials with lower carbon footprints, designing packaging that is easy to recycle, and planning product take‑back schemes. The goal is to minimise resource use and pollution while still delivering quality products.

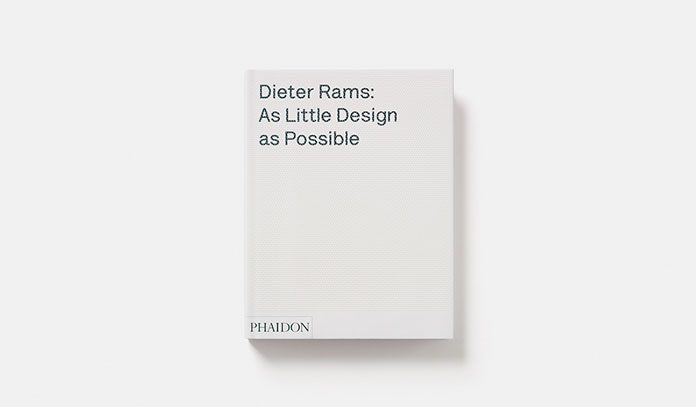

Minimalism: As Little Design as Possible

“Less, but better” captures the essence of minimalism in design. Removing non‑essential elements clarifies function, reduces production costs, and simplifies maintenance. Minimalism does not mean sacrificing functionality; rather, it concentrates on the essential aspects so that products are not burdened with extraneous features. This aligns with the principle of not making users think: simple, uncluttered interfaces help people accomplish tasks without confusion. Similarly, focusing on clarity and logical flow while avoiding unnecessary complexity is crucial. In physical products, minimalism can translate into fewer parts, modular construction, and timeless forms. The challenge is to achieve simplicity without creating austerity; warmth and personality can coexist with restraint. A minimalist approach also supports sustainability by using fewer materials and making products easier to recycle.

Design as a Force for Social Good

Design has a profound influence on social equity. Inclusive, universal design aims to create products and spaces usable by people of different abilities, ages, and cultures. Social design is committed to building a culture of acceptance and mutual respect, democratising access to quality goods and services, and empowering communities. This can involve designing assistive technologies, accessible public spaces, or communication strategies that raise awareness about issues like climate change or health. Designers must consider diversity from the outset—incorporating varied perspectives leads to solutions that work for more people. Inclusive design is not a separate principle; it permeates all aspects of good design, reminding us that empathy and social responsibility are integral to our profession.

How to Apply Good Design Principles in Practice

Good design does not happen by accident. It emerges from a disciplined process rooted in research, iteration, and collaboration. The following steps provide a framework for applying the principles described above.

1. Conduct Deep User Research

Understanding users is the foundation of good design. User‑centred design is an iterative process that involves understanding real users’ pain points through testing and feedback. You should look beyond surface‑level demographics and study behaviours, motivations, and goals. Create personas to represent different user types and base design decisions on real data rather than assumptions. Tools like analytics platforms or moderated usability tests can help identify where users struggle. Competitive analysis reveals gaps and opportunities. The goal of research is to empathise with users so that you can design solutions that genuinely improve their lives.

2. Define the Problem and Align with Business Goals

After gathering insights, define the core problem you are solving. Identifying problems comes from thorough research and testing, not designer intuition. A clear problem statement guides ideation and prevents feature creep. Align the solution with business objectives; the design should create value for both users and organisations. When business goals and user needs overlap—like making checkout smoother to increase conversions—everyone benefits.

3. Generate Ideas and Prototype

Brainstorm ideas that address the defined problem. Use sketches or wireframes to visualise the user journey. Focus on clarity, ease of use, and logical flow. Keep the prototype minimal at first; you can add features later if testing shows they are necessary. Invite stakeholders and developers into the process early to ensure feasibility and buy‑in. Remember that innovative design must develop alongside technology—stay informed about new materials and tools that could help solve the problem better.

4. Test and Iterate

Usability testing is essential. Test prototypes with real users; observe where they hesitate, misunderstand, or abandon tasks. Gather feedback and refine your design, addressing critical issues first. Micro‑interactions and animations can provide useful feedback to users. Iteration is not a one‑time event; continue refining the product even after launch, as user needs and technologies evolve.

5. Design for Sustainability and Longevity

Early in the process, consider how to minimise environmental impact. Conduct a life‑cycle assessment to identify stages where resource use and emissions can be reduced. Choose materials that are renewable, recycled, or recyclable. Design products for repairability and modularity so that users can replace parts instead of discarding the whole item. Adopt manufacturing processes that reduce waste, such as 3D printing or on‑demand production. These decisions can also reduce costs and differentiate your product in a market where consumers increasingly value sustainability.

6. Communicate Honestly and Transparently

During marketing and product communication, set correct expectations. Avoid exaggerating features or using dark patterns. Provide clear information about how to use the product and what benefits users will receive. Honesty builds trust and reduces returns. Transparency about sourcing, labour conditions, and environmental impact enhances credibility.

7. Plan for Inclusivity

Incorporate inclusive design principles from the beginning. Ensure that people with different abilities, ages, or cultural backgrounds can access and enjoy your product. Conduct research with diverse participants and test for accessibility. Consider language support, contrast, and readability, physical ergonomics, and cultural sensitivities. Inclusive design not only expands your audience but also promotes social equity.

Personal Insights and Emerging Trends

Working as a design critic reveals patterns behind products that resonate with people. One observation is that the most compelling designs often appear simple yet hide complex thinking. Designers like Jony Ive have always spoken about removing barriers until the product feels inevitable. In my view, the future of good design will revolve around three interconnected trends: intelligent adaptation, sustainable innovation, and humanised minimalism.

First, intelligent adaptation means products that learn and adapt to users. AI‑driven interfaces will predict needs, but they must remain transparent so users feel in control. Tools like generative design can explore countless configurations while respecting constraints like material efficiency. Second, sustainable innovation will continue to shape aesthetics. Recycled and bio‑based materials, modular systems, and circular business models will influence how products look and function. Brands that embrace visible sustainability—showing seams, modular joints, or reclaimed textures—signal authenticity. Finally, humanised minimalism will replace austere minimalism. Designers will maintain restraint but introduce warmth through organic forms, tactile surfaces, and playful color accents. This balance will allow products to feel both timeless and inviting.

Good design is not limited to consumer products. Architecture, urban planning, and communication all benefit from the same principles. For example, inclusive city parks, easy‑to‑navigate airports, and clear public signage embody the values discussed here. Beyond aesthetics and functionality, good design fosters wellbeing, community, and respect for the planet. It invites us to slow down, appreciate our surroundings, and make conscious choices. As a design community, we should continue to question assumptions, learn from users, and embrace humility.

The Bottom Line

Good design is a commitment to users, to the planet, and to the future. It demands curiosity, empathy, and discipline. When designers follow principles that prioritise people, embrace sustainability, and respect honesty, they create products that stand the test of time. These principles are not rigid rules but guides that remind us to think critically and act responsibly. As consumers, we have the power to support companies that practice good design by choosing products that align with our values. As designers, we have the responsibility to push boundaries while remaining humble and attentive. The next time you pick up a beautifully crafted object or navigate an intuitive app, take a moment to appreciate the invisible work that makes good design not only possible but indispensable.

Browse WE AND THE COLOR’s Design section for more. Feel free to check out our selection of the top 10 graphic design trends for 2026.

Subscribe to our newsletter!